I build robots for fun.

Rick Sanchez

It’s common knowledge that in 2019 the NSA decided to open source its reverse engineering framework known as Ghidra. Due to its versatility, it quickly became popular among security researchers. This article is one of many to come dedicated to covering the technical details of the ghidra_nodejs plugin for Ghidra, developed by our team. The plugin’s main job is to parse, disassemble and decompile NodeJS Bytenode (.jsc) binaries. The focus of this article is the V8 bytecode and the relevant source code entities. A brief description of the plugin is also provided, which will be expanded upon in greater detail in subsequent articles.

Sooner or later, everyone comes across programs written in JavaScript, generally called scripts. JavaScript is a fully-fledged language with its own ECMA Script standard, and can be frequently found executing server-side on the backend as well as in the browser.

Scripts are executed using a special program called a JavaScript engine. Many implementations have been built over the years: V8, SpiderMonkey, Chakra, Rhino, KJS, Nashorn, etc.

Scripts are distributed as plain text, i.e. the source code is available. Therefore, all engines fullfill the following criteria:

- Read and parse a script into an abstract syntax tree (AST).

- Compile the AST into machine code.

- Run the machine code.

Or

- Read and parse the script into an abstract syntax tree (AST).

- Compile the AST into bytecode.

- Compile the bytecode into machine code.

- Run the machine code.

To reiterate, scripts look like and are distributed as simple text. Therefore, if an application is not open source, there is an issue of protecting code from prying eyes for developers of server-side applications written in JavaScript. With the most widespread method currently used being obfuscation.

The authors of this article stumbled across another method of protecting JavaScript code during one of our assignments. The application in question was distributed as a binary file with the .jsc file extension for the Node.js runtime environment, to be run server-side, and consisted of serialized V8 bytecode. As will be explained below, this is a native Node.js feature used by the bytenode package. Our goal consisted of investigating the functionality of this JSC application and finding any underlying vulnerabilities or undocumented features.

No off-the-shelf tools for working with serialized JSC files were found. That is of course, apart from Node.js itself. Node.js has the --print-bytecode flag, but the results leave a lot to be desired. A bare-bones function disassembler without cross-references or any additional information about objects is not the ideal tool to aid in a fully-fledged reverse engineering effort via static code analysis. Therefore, we had to reinvent the wheel and roll our own tool.

Node.js + bytenode

Stop digging for hidden layers and just be impressed!

Rick Sanchez

The Node.js platform is an open source JavaScript environment, built on top of the Chrome V8 engine. Generally, its used to create server applications in JavaScript, and is used by many major companies in their projects.

One of the core features of Node.js is the ability to add packages. i.e. external libraries form the Node.js ecosystem, to scripts. The node package manager (npm) allows access to more than half a million open-source packages.

The bytenode package from Osama Abbas enables users to store serialized v8 bytecode of JavaScript applications, which can be executed without the original source code present with no negative impacts on performance.

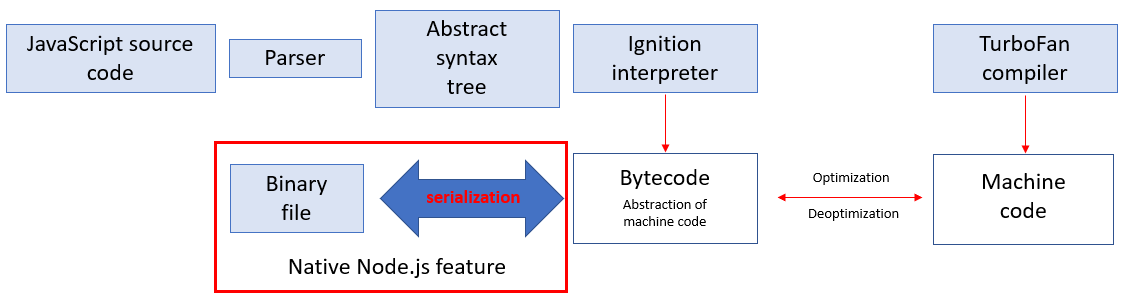

Let’s take a look at the V8 compilation pipeline, post 2017.

To quote the article Know your JIT: closer to the machine [RU]:

Previously [pre 2017] there was no Ignition interpreter. Google originally believed that an interpreter was not necessary — JavaScript was sufficiently compact and interpretable — gains from an interpreter would be negligible. <…> In 2013–2014 people began to use mobile devices more than desktops to access the internet. The majority of those phones were not iPhones and had low processing power and small amounts of ram.

“Feeble” smartphones began to spend more time analyzing script source code than running it. Then the Ignition interpreter appeared. The introduction of bytecode allowed a decrease in memory consumption and parsing overhead.

The Ignition bytecode interpreter is a register machine with an accumulator. It includes a set of instructions and registers. It turns out that bytecode and objects interacting with it in their classes are stored within the V8 engine structures. Therefore, there is no longer any need to constantly analyze script source code. Serialization is the ability of the V8 engine to store bytecode and the structures linked with it in binary representation. Deserialization (the reverse process) allows binary data and the objects linked with it to be transformed into bytecode.

The bytenode package uses the native feature of the Node.js platform, the ability to get serialized code. In Node.js the compilation takes place using the vm module and Script function. Starting from version 5.7 the vm module has a property called produceCachedData in vm.Script. This property allows bytecode to be stored in a cache. Example for versions higher than 10:

let hello = new vm.Script("Text with JavaScript code", {produceCachedData: true});

let helloBuffer = hello.createCachedData();After running this code, the serialized data will be located in helloBuffer.

The bytenode package stores serialized data in files with the .jsc extension. Using the same package a file with the .jsc extension (from now on we will refer to such files as JSC files) can be launched for execution, as described in the article How to Compile Node.js Code Using Bytenode?.

JSC files have proven to be a good method of concealing script source code from prying eyes.

What can be done?

Wubba lubba dub dub.

Rick Sanchez

Reading various literature on Node.js and the V8 engine, static analysis of the sources has led to the following thoughts:

- A parser for JSC file headers is required.

- We need to (try to) look into the inner workings of the V8 engine, into its specific objects within whose framework bytecode is created. As a result, we need to create a loader for the disassembler we have created, which will create similar specific objects and display the instructions and operands (preferably in a format like the one in Node.js when we launch the platform with the “–print-bytecode” flag in the JSC file).

- An ambitious idea is to attempt to write a decompiler for the bytecode created. That is, to implement a register machine with an accumulator, working with bytecode, into the output of a C-type decompiler. Therefore, the disassembler chosen was the open-source Ghidra with its versatility in terms of different structures and an “out-the-box” decompiler.

Before knocking on the open door with the “JSC file” nameplate, we will try to describe some of the concepts concerning the V8 engine, armed with the Node.js source code.

The V8 universe

The universe is so big, Morty, that nothing in the world matters.

Rick Sanchez

The arrangement of the V8 engine is not straightforward. Here we are only going to look at the entities linked to the bytecode of the Ignition interpreter.

Isolate is an independent copy of the V8 runtime environment, including its own heap. Two different instances of Isolate will work in parallel, and they can be regarded as completely different isolated instances of the V8 runtime environment.

Context is a separate area for the variables of a single JavaScript application. Each JavaScript application running in the same Isolate needs its own context. The context is used so that applications do not become mixed up with one another, for example, by modifying the embedded objects.

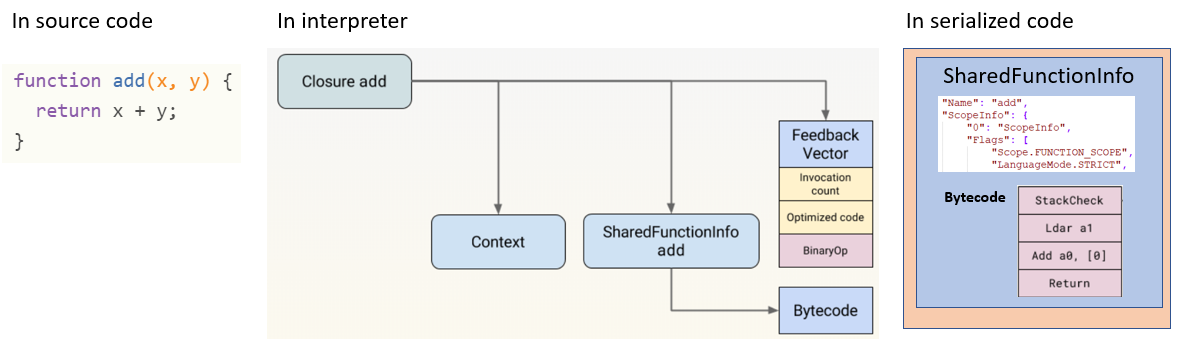

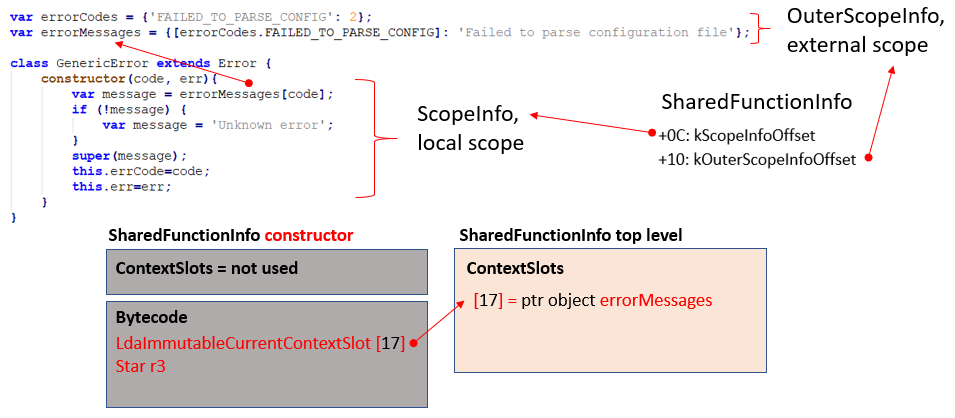

Closure is a function which stores its external variables and can gain access to them. In JavaScript, all functions start out as closures: to put it simply, all fragments of code between curly brackets are closures. Essentially, all JavaScript source code is a bunch of various code in curly brackets which can be presented in the form of a Closure structures array. Figure 2 shows how Closure looks in the source code, is processed by the interpreter and stored in serialized code.

An important point for us: at the object level in serialized code, Closure looks like the SharedFunctionInfo object. Analysis showed that all serialized data looks like a Russian “matryoshka” doll made of SharedFunctionInfo objects which refer to one another.

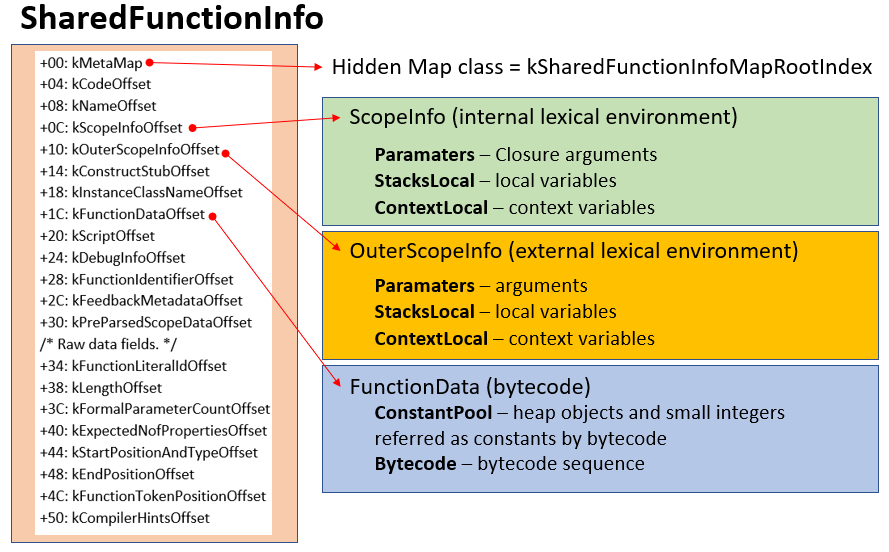

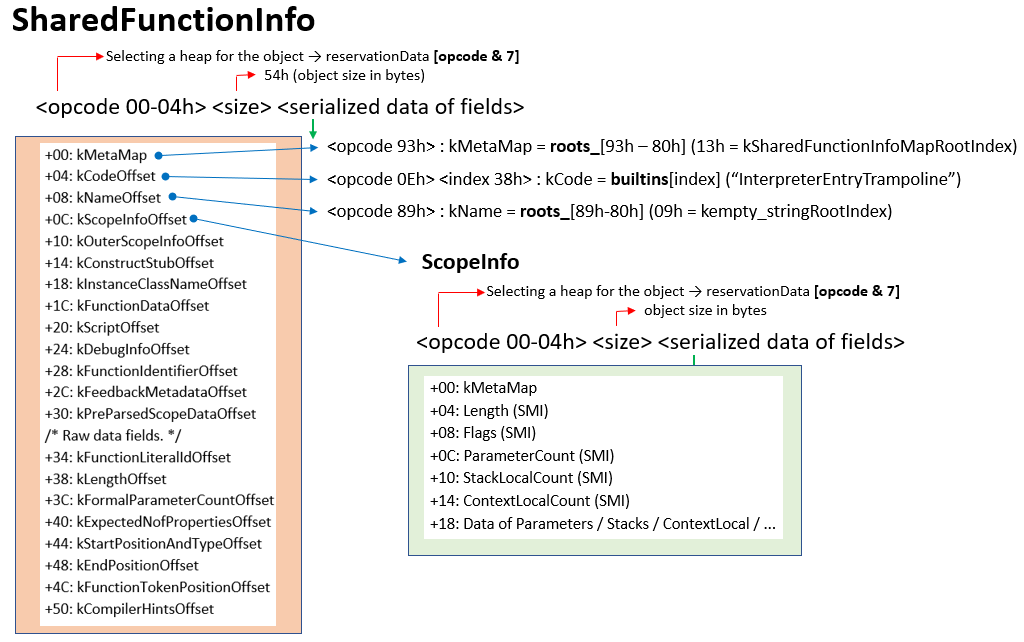

When serialized, a SharedFunctionInfo object looks like a large structure which combines the different entities required for processing bytecode. Some of them are show in Figure 3.

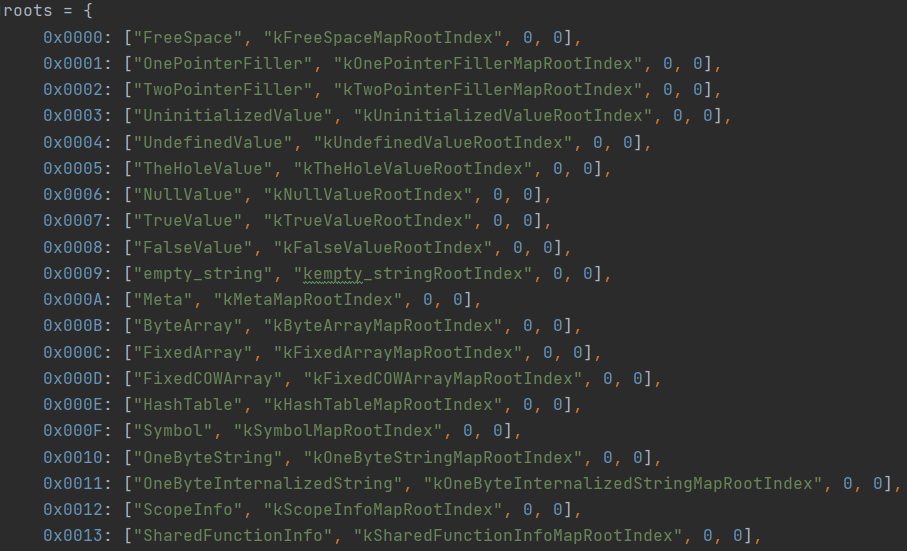

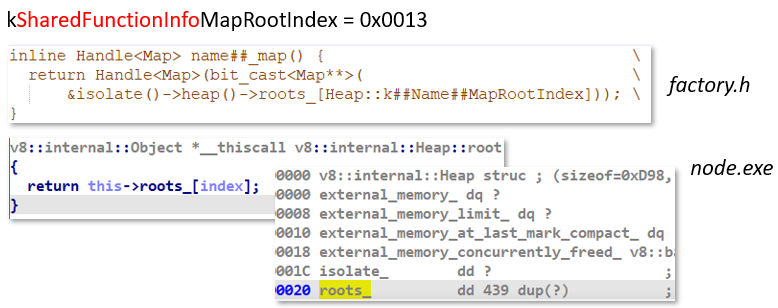

Hidden map (hidden class). All objects created by the interpreter (for example, the same SharedFunctionInfo) are constructed not from scratch but based on a hidden class (Map class), which contains a set of standard properties. There are already hidden classes within the engine, they are created during runtime. The links to them are stored in the roots_ array of the Heap object.

And when serialization takes place (or deserialization), the link to the hidden class is stored as the index of the roots_ array. In node.exe (for version 8.16.0) the index for the hidden class kSharedFunctionInfoMapRootIndex equals 0x13 (see Figure 5). The quantity and contents of elements in roots_ may change from version to version of the V8 engine in Node.js. Therefore, it is important to pay attention to the version of the V8 engine when deserializing a JSC file.

LexicalEnvironment is a repository for data in memory and a mechanism for extracting this data when addressed. The environment may be internal (ScopeInfo structure) and external (OuterScopeInfo structure). Quote (link[RU]):

“Each time that a function is called in the program, within the interpreter the special LexicalEnvironment lexicon is created that is associated with that call. All definitions of the constant, variables, and so on within the function are automatically written to the lexicon. The name of the definition (the identifier, that is, the name of the constant, variable and so forth) becomes a key, and the value of the definition becomes a value in the lexicon. The definitions include arguments, constants, functions, variables, and more.

<…>

The external environment in relation to the function is the environment in which the function was declared (and not called!).”

And in the same place: [SI1] “…the interpreter carries out a search for the value of the identifier not only in the local lexical environment (the one where the identifier is being used), but also in the external environment. The search begins from the local environment, and if the required identifier is not found in it, then the search goes on up to module level, and then up to global level.”

In the example in Figure 6, the constructor function is making a call to the errorMessages variable. In the interpreter, the constructor function is represented by the SharedFunctionInfo structure having ScopeInfo (local variables) and OuterScopeInfo (external variables). In this case OuterScopeInfo stores the address of the ScopeInfo structure of the SharedFunctionInfo parent where the declaration of the errorMessages variable is located.

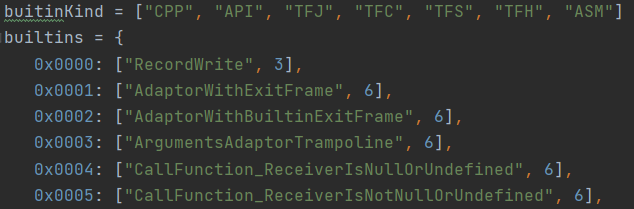

Built-ins (embedded functions) are V8 engine embedded functions. By themselves they can be implemented in different ways (builtinKind) and are placed in the global array (builtins) of the V8 engine.

Deciphering the methods of implementing the builtinKind enumeration:

- CPP is the Builtin embedded function, written in C++.

- API is the Builtin embedded function, written in C++ with the use of API callbacks.

- TFJ is the Builtin embedded function, written in Turbofan (JS linkage).

- TFS is the Builtin embedded function, written in Turbofan (CodeStub linkage).

- TFC is the Builtin embedded function, written in Turbofan (CodeStub Linkage and custom descriptor).

- TFH is the Builtin embedded function, written as a handler for Turbofan (CodeStub linkage).

- ASM is the Builtin embedded function, written in platform-independent assembler.

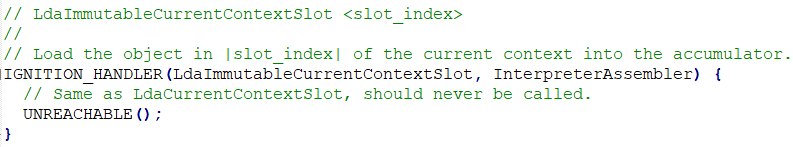

Embedded functions may include mathematical functions, string-to-numeric conversion functions, and others. Embedded functions are called directly from bytecode: StackCheck, Construct, ConsoleLog, CreateGeneratorObject, JsonParse, and other.

FunctionData (bytecode) is a structure that stores the so-called ConstantPool array for constants and the bytecode itself. As was mentioned early, the V8 interpreter is a register machine with an accumulator. The interpreter uses the following registers (shown below is the spelling of the registers accepted for display in a listing with bytecode):

- <this>, <closure>, <context> are internal registers of the interpreter that are required for its work (roughly speaking, <closure> stores a reference to SharedFunctionInfo, <context> stores a reference to ScopeInfo).

- The ACCU accumulator register.

- The registers of arguments a0, a1, a2… and registers of functions r0, r1, r2… Each register within bytecode is coded with four bytes. The most significant bit determines the type of register, aX or rX. The remaining bits are the number of the register. Therefore, the quantity of function registers may be up to 0х7FFFFFFB items, and argument registers 0х7FFFFFFE (only if there is sufficient memory for storing register values in the interpreter).

Each bytecode instruction reads or modifies a condition of the ACCU accumulator. The operands of the instruction are r0, r1, and so on, which are either indexes in ConstantPool (in disassembler they look like numbers in square brackets), or indexes to variables from the arrays StackLocal/ContextLocal of the structures of the lexical environment ScopeInfo/OuterScopeInfo.

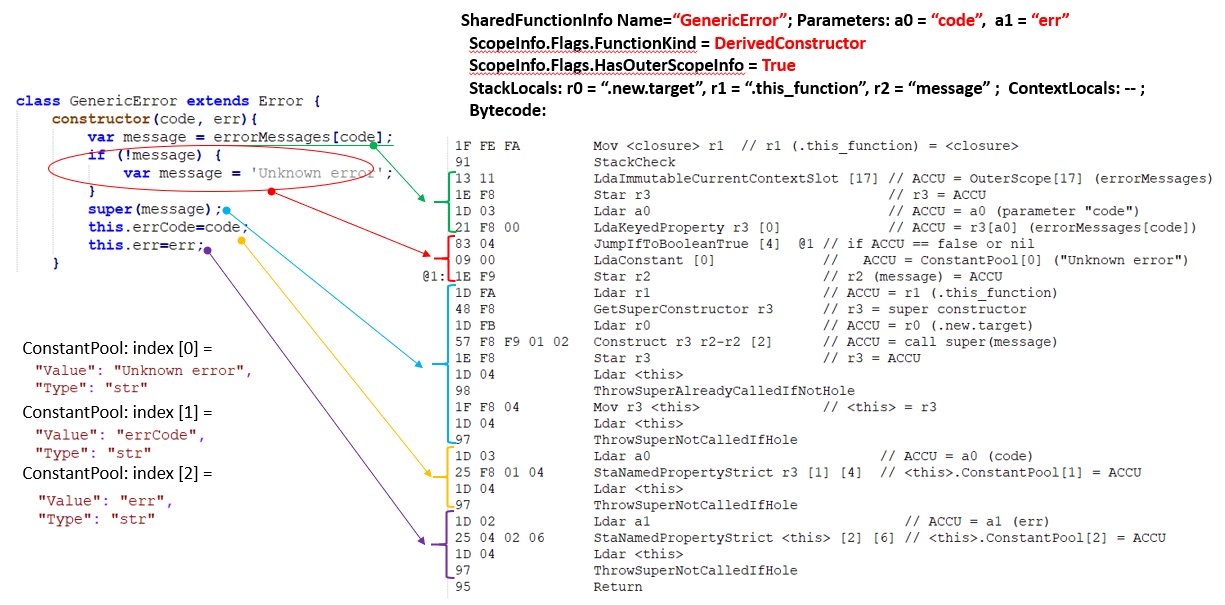

Let’s evaluate the scale of parsing FunctionData using the example of the disassembly of the Constructor function for the GenericError class inherited from the base class Error. Figure 8 on the left shows the source code of the GenericError class constructor, on the right its bytecode in the SharedFunctionInfo object.

The SharedFunctionInfo structurefor the constructor function will have the name “GenericError.” The ScopeInfo structure Flags field tells us that this function is a constructor of the constructor class (Flags.FunctionKind =DerivedConstructor) and it has an external lexical environment (Flags.HasOuterScopeInfo = True). The function takes two arguments a0 (“code”) and a1 (“err”). The function has StackLocals internal local variables: r0 (special name “.new.target“), r1 (special name “.this_function“), r2 (a variable with the name “message“). Special names always start from a period, and they are required for the V8 engine when creating machine code from bytecode. The function does not have the ContextLocals context variables. If StackLocals are local variables, then ContextLocals are local context variables. This is due to the fact that V8 regards every SharedFunctionInfo as a certain context with its own bytecode and local variables. And we can call variables of the current function via the context, or the context of another function, or a specially created context (especially when the asynchronous calls async/await are being used).

The bytecode instructions then follow. The instructions follow the same sequence as the lines in the script source code. A short description of each instruction can be found in the Node.js source code.

In our version of the V8 engine, there were 167 instructions, with several dozen often being used. The peculiarity of the bytecode instructions is due to the fact that bytecode is not an end in itself for the whole engine but only a springboard for creating machine code with the TurboFan compiler. Therefore, certain specific operands of the bytecode and unusual instructions are redundant: their task is to display the script source code in a stricter and more typified form. That is to say, having the disassembly of the bytecode in our hands, it is POSSIBLE to restore the script source code. Manually it is possible. Our task is to try to do this automatically using a decompiler.

Header of the JSC file

Morty relax, it’s just a bunch of ones and zeros out there

Rick Sanchez

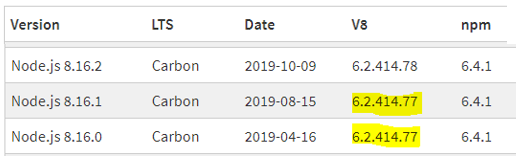

We should say right away that version 8.16 of Node.js was the one studied (version 6.2.414.77 of the V8 engine). All versions of the software platform are available at the official site.

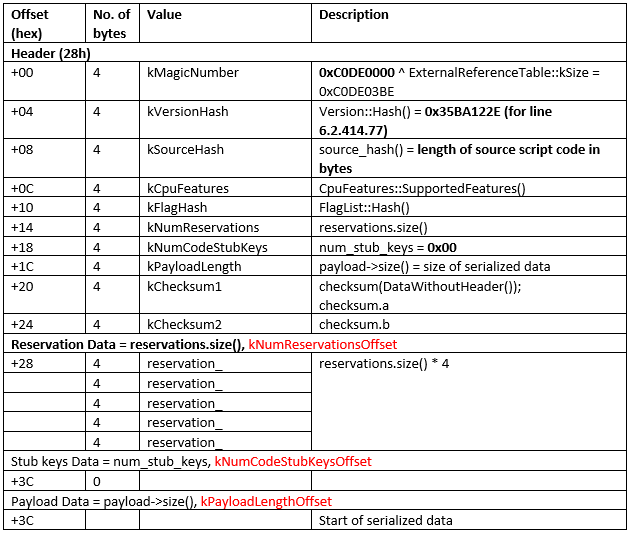

The JSC file consists of a header and serialized data. The table shows the structure of the header.

What is worth paying attention to? First of all, the field kVersionHash, which stores the hash from the version of the V8 engine, presented in string form. For example, for 6.2.414.77 (this is the engine used in Node.js version 8.16.0) the value of hash will be 0x35BA122E. The kVersionHash field is one of the mandatory fields which Node.js checks when launching a JSC file. The V8 engine does not stand still, with new releases coming out and in due course the format of serialized data changing. Therefore, tracking the version when deserializing is a mandatory condition.

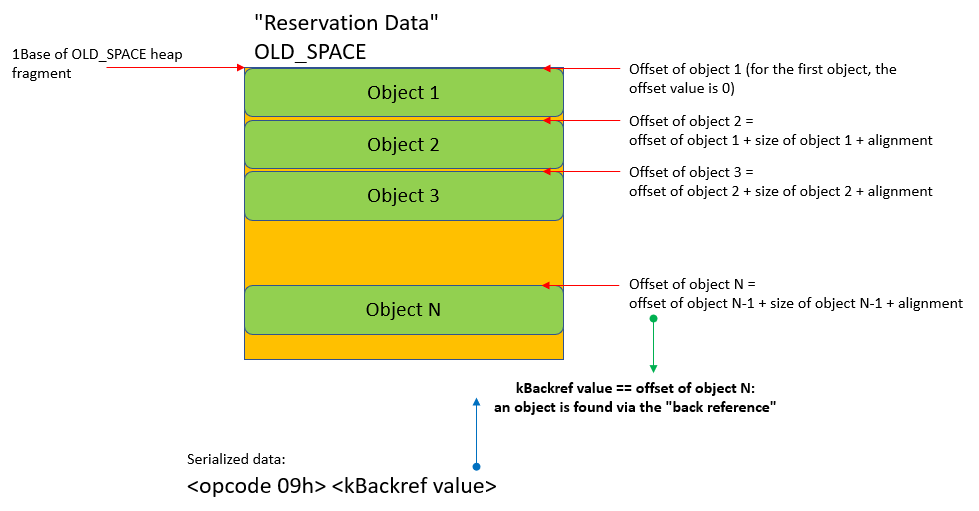

Second, it’s worth taking a look at the kNumReservationsOffset field. This is the number of records in the “Reservation Data” (heap fragments managed by the V8 engine). Each record is a number of bytes for the allocated memory fragment on the heap. Let us explain what for and why this is. When analyzing a script (still at the compilation stage in bytecode) all JavaScript values in the V8 engine are presented as objects and arranged in the heap, irrespective of whether they are objects, arrays, numbers, or strings. The objects are arranged in the heap behind one another, end to end.

During serialization, objects are processed in a special way and written to the binary stream in the same order as they are arranged in the heap. And if the object has already been serialized and is encountered again (different objects can have common objects; for example, some object strings with an identical value), then the object is not duplicated in the binary stream but is written as a link to its first entry. And this link will be a number heap offset (this technology is known as Pointer Compression, when the pointer can be written in the form of an offset relative to the base). When deserialization takes place, the V8 engine creates objects from binary data in the same order and correctly processes link offsets.

Conclusion. During deserialization our loader MUST process the stream of serialized data in the same way as the V8 engine (emulating the arrangement of orders in the heap).

The stream of serialized binary data itself begins immediately from offset 0x3C. That will be discussed in the next part.

V8 engine serialized data loader

Hate the game and not the player, son.

Rick Sanchez

In telegraph style, we are going to quickly talk about how the V8 engine loader works. It was its logic that we focused on when creating our loader in the plugin. A detailed article on the loader will appear later.

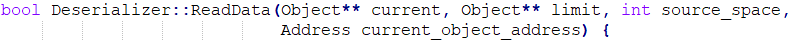

1) Where does the reading of the serialized data take place? We can find the function in deserializer.cc in theNode.js source code.

Our loader follows the logic of this function when parsing serialized data.

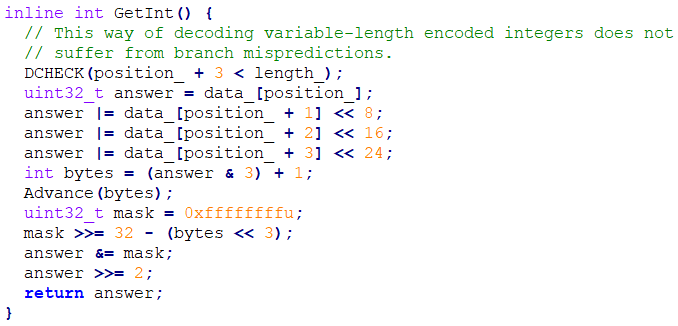

2) There are several number-coding formats that the loader needs to know about:

- Number storage format: variable-length encoded (GetInt function in the file snapshot-source-sink.h inthe Node.js source code). This format is used in serialized data, for example, to store the sizes of objects.

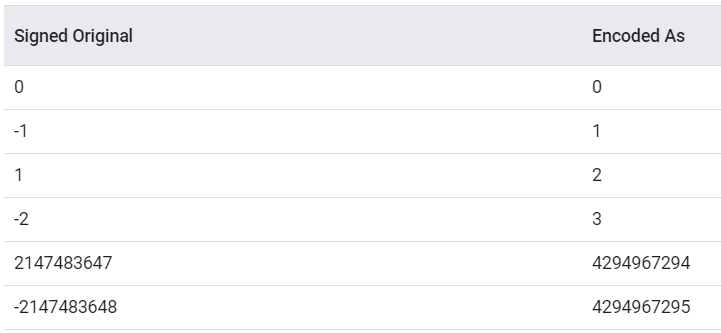

- Number storage format: zigzag encoding (file source-position-table.cc inthe Node.js source code). It includes two methods of encoding. The first is variable-length integer encoding (a popular method of “compressing” integers; the idea is 7-bit encoding: one byte contains 7 bits of information, and the most significant bit indicates whether the following byte contains useful information). The second is the zigzag method of encoding positive and negative numbers (the sign bit from the most significant bit of the number is transferred to the least significant bit). Structure data from the SourcePositionTable (a special table of matches, where string numbers of the source script code match offsets within the bytecode) is stored in serialized data.

- Number storage format: SMI (small integer). In the 32-bit version of the V8 engine the least significant bit in the SMI number signifies the following: 1—the number is a pointer, 0—this is an ordinary number. In order to gain the SMI value, the displacement must be shifted one bit to the right of “SMI>>1..” The numerical values of fields within objects (for example, the Length field in the FixedArray object) is stored in SMI format in serialized code.

3) Format of serialized data:

<opcode> (one byte) <opcode data> (N byte)

In the V8 engine, each object consists of a set of fields (a direct analogue with the fields of a class in object-oriented programming). Each field can be a “pointer” to another object. This object can be embedded (stored in the roots_ array of the Heap object), or already created in the early stages of deserialization (a so-called back reference must be stored for it), or is a new object (in this case the deserialization of its fields is launched).

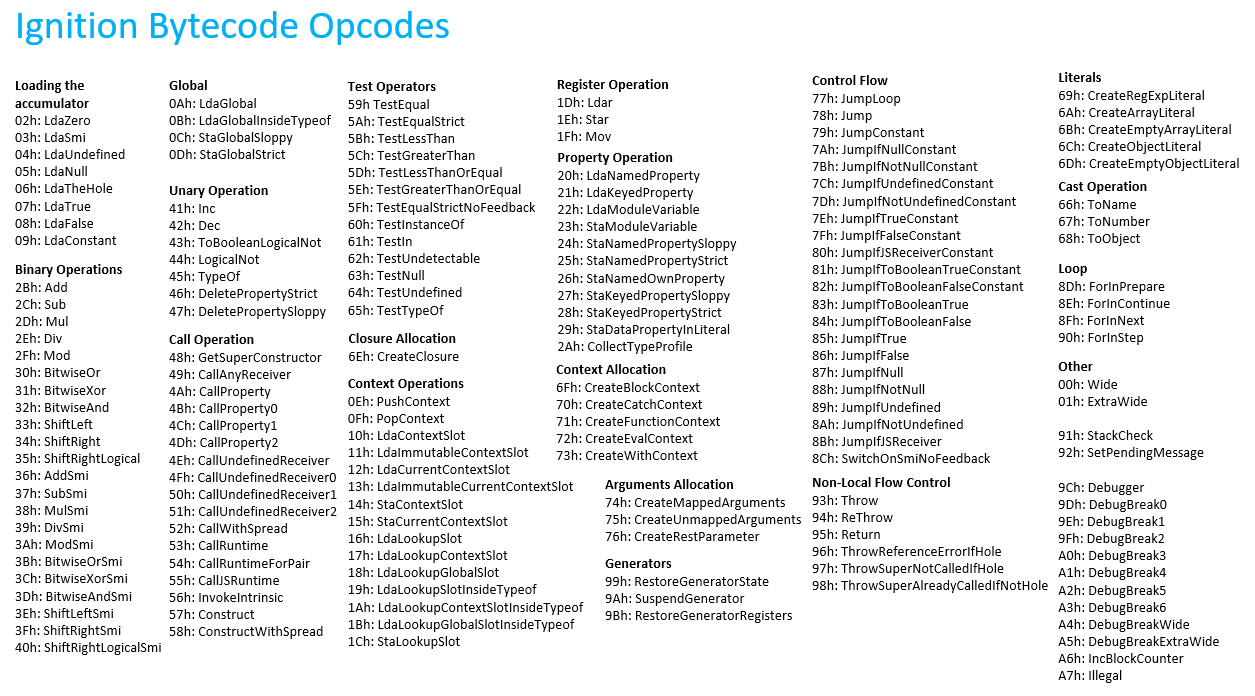

4) What opcodes are implemented in the loader (opcodes enumerated here we have implemented in our plugin):

- 00h-04h (kNewObject) = creation of a new object. The object is always placed in the Reservation Data (heap fragments managed by the V8 engine). How is a specific fragment chosen? Using a simple operation: opcode & 7. The following fragments exist:

- 0 = NEW_SPACE (“new” JavaScript objects are placed in this heap fragment, where objects gathered using copying collector also end up)

- 1 = OLD_SPACE (“old” JavaScript objects are placed in this heap fragment; there may also be pointers here to the fragment with “new” JavaScript objects)

- 2 = CODE_SPACE

- 3 = MAP_SPACE

- 4 = LO_SPACE (for storing large objects)

- 08h-0Ch (kBackref) = back reference to object. In order to reduce the size of serialized data, there is no need to reserialize already serialized objects. To do so, the so-called back references are used. All objects are created in their heap fragments: NEW_SPACE, OLD_SPACE, CODE_SPACE, MAP_SPACE, LO_SPACE. Therefore, there are also five opcodes for back references, for each type of heap fragment. All the objects in the cloud fragment are located sequentially one after another. It turns out that the value of the back reference is essentially the offset of the object within the heap fragment.

Our plugin loader acts in a similar way: it takes a snapshot of the created objects for each heap fragment. The loader also keeps track of the sizes of objects, taking alignment into account. When a back reference appears in the serialized data, the loader finds the object by going through the list of created objects. The object found is written in parallel to the “hot links” array (hot_objects, a small array, only seven elements). The hot_objects array is required for processing the kHotObject opcode.

- 05h (kRootArray) = find a Map-class object in the roots_ array of the Heap object and write a pointer to the object in the current offset of the deserialized object. The index for the roots_ array is located in the opcode data. The object itself is written in parallel to the hot_objects array. The hot_objects array is required for processing the kHotObject opcode.

- 0Dh (kAttachedReference) = find an object in the attached_objects array and write a pointer to the object in the current offset of the deserialized object. For our plugin loader, the attached_objects array contains one element with a zero (it is not used).

- 0Eh (kBuiltin) = find an object in the builtins array and write a pointer to the object in the current offset of the deserialized object. An example of a common embedded object is InterpreterEntryTrampoline.

- 0Fh (kSkip), 15h-17h (kWordAligned, kDoubleAligned, kDoubleUnaligned) = our loader emulates these opcodes for alignment of data on the heap.

- 18h (kSynchronize) = this is the deserialization breakpoint. The deserialization process is completed.

- 19h (kVariableRepeat) = is used for repetition of the previous deserialized value. The number of retries is transmitted in the opcode data.

- 1Ah (kVariableRawData) = used when it is necessary to write “raw” data into the object. The size of the data must be aligned (found in the opcode data).

- 38h-3Fh (kHotObject) = find an object in the hot_objects array and write a pointer to the object in the current offset of the deserialized object.

- 4Fh (kNextChunk) = this is an instruction to the V8 engine to “proceed to the next reserved chunk.” The instruction is related to fragments of the “Reservation Data” heap and to placing so-called FILLER objects in them. Fillers reserve memory in the heap fragment. The loader takes these FILLER objects into account for the correct calculation of the values of back references.

- 80h-9Fh (kRootArrayConstants) = find an object in the roots_ array.The index for the roots_ array is calculated using the formula “value – 80h.” The pointer to the object found is written into the current offset of the deserialized object.

- C0h-DFh (kFixedRawData) = is used when it is necessary to write “raw” data (a fixed number of bytes) into the object. The number of bytes calculated using the formula “value – BFh.”

- E0h-EFh (kFixedRepeat) = is used for repeating the previous deserialized value a fixed number of times. The number of repeats is calculated using the formula “count = (value – DFh).”

5) What objects the loader in the plugin parses in the course of serialization:

- SharedFunctionInfo (a closure object)

- ScopeInfo and OuterScopeInfo (lexical environment)

- FunctionData (object with bytecode)

- FixedArray, FixedCOWArray (a “key-value” lexicon; objects themselves can be a key)

- ConsString (a binary tree, where leaves, for example, are ordinary ConsOneByteString string objects)

- HandlerTable (exception handlers)

- SourcePositionTable (special table of matches where string numbers of the source script code match offsets within the bytecode)

The parsing of enumerated objects is necessary in order to correctly form data for the bytecode disassembler and for the subsequent work of the decompiler.

Plugin disassembler

— Why would anyone do this?

Rick and Morty

— The reason anyone would do this is, if they could, which they can’t, would be because they could, which they can’t.

And again, we are going to briefly go through how the plugin disassembler works. Detailed articles on the processor module will appear later.

1) Where bytecode is located: in SharedFunctionInfo objects created by the loader:

- In the object SharedFunctionInfo → FunctionData:

- The kBytecode field = the bytecode itself.

- The kConstantPool field = array made up of constants, strings, lexicons, and other objects.

- The SourcePositionTable field = table of matches, where string numbers of the source script code match offsets within the bytecode.

- kHandlerTable = table with exception handlers.

- In the object SharedFunctionInfo → ScopeInfo, the lexical environment for the bytecode of the function is situated.

2) What a V8 bytecode instruction looks like:

- Width (optional, 1 byte):

- 0 —Wide

- 1 — ExtraWide

- Opcode (1 byte)

- Operands (can be coded with 1, 2, or 4 bytes each)

// TestEqualStrict <src>

// 00: Wide

// 5a: TestEqualStrict, test if the value in the <src> register is less than the accumulator

// 00 02: a1 - <src>

// 0x145 - slot_index

00 5a 02 00 45 01 TestEqualStrict.Wide a1, [325]

Several basic groups can be identified by their types of instructions: loading into the accumulator (prefix Lda), writing from the accumulator to a different place (prefix Sta), working with registers (Mov/Ldar/Star), mathematics (prefixes Add/Sub/Mul/Div/Mod), boolean operations (BitwiseOr/ BitwiseXor/ BitwiseAnd/LogicalNot), offset (prefix Shift), multipurpose embedded instructions (prefix Call/Invoke/Construct and without the prefix StackCheck/TypeOf/ToName/ToNumber/ToObject/Illegal), comparison instructions (prefix Test), creation of objects (prefix Create), conditional jumps (prefix Jump), loops (prefix For), instructions to generate exceptions (prefix Throw), debugging instructions (prefix Debug), branching (SwitchOnSmiNoFeedback).

Conclusion. Node.js version 8.16.0 provides 167 instructions.

Numeric operands in the instruction have a reverse order of bytes (little-endian).

3) The processor module for the plugin was written for the Ghidra framework. The bytecode instructions are described in SLEIGH. The description of the analyzer and loader and redefinition of the p-code for certain V8 operations are executed in Java. When loading the file into Ghidra, the loader parses the JSC file breaking it into functions and defining the entities required for analysis and decompilation.

4) It was difficult to implement the function arguments and registers precisely as in Node.js. There was an option to implement them as registers or make a repository like a stack for each function. To better match the output of Node.js and for ease of perception, the decision was made to use the register model, although it did impose limits on the number of registers which a function can work with (a0-a125, r0-r123).

The result of all this, our work, became the plugin ghidra_nodejs for the Ghidra disassembler.

Epilogue

You know the worst part about inventing teleportation? Suddenly, you’re able to travel the whole galaxy, and the first thing you learn is, you’re the last guy to invent teleportation.

Rick Sanchez

A great adventure needs a great ending!

Rick Sanchez

There’s a phrase in the presentation DLS Keynote: Ignition: Jump-starting an Interpreter for V8: “JavaScript is hard! V8 is complex!” We have to agree that the V8 machine (in particular, the Ignition interpreter) is not simple. And even an attempt to understand it is worthy of attention.

As a result, we completed our job of analyzing the server application. We were able to obtain readable code. We hope that this tool will help our readers when working with serialized bytecode from the V8 engine.

Many thanks to Vladimir Kononovich, Vyacheslav Moskvin, Natalya Tlyapova for researching Node.js and developing the module.